Sweet Potato Pie & Black Genius: The George Washington Carver Story

Extended Readings from the Igotchu x Urban Intellectuals Seasonings Collaboration — where flavor meets history, and every bite tells our story.

Explore Fannie Lou Hamer | Georgia Gimore | Sweet Auburn | George Washington Carver

Igotchu Seasonings X Urban Intellectuals Collaboration, 4 Flavor Seasonings + History Pack!

Introduction

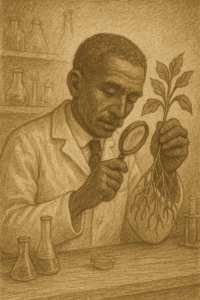

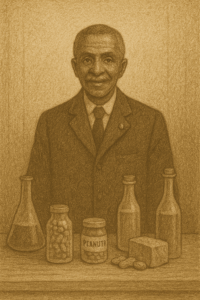

George Washington Carver is remembered by many as “the peanut man,” but that nickname barely scratches the surface of his brilliance. He was an artist, scientist, educator, environmentalist, and spiritual visionary who believed deeply that nature held solutions to humanity’s problems.

George Washington Carver is remembered by many as “the peanut man,” but that nickname barely scratches the surface of his brilliance. He was an artist, scientist, educator, environmentalist, and spiritual visionary who believed deeply that nature held solutions to humanity’s problems.

Carver turned simple crops like peanuts and sweet potatoes into hundreds of innovations — not just foods but paints, dyes, medicines, industrial materials, and even plastics. His genius wasn’t in chasing patents or fortune but in service. He wanted poor farmers, especially Black sharecroppers struggling in the South, to see abundance where others saw only scarcity.

That’s why this Sweet Potato Pie Seasoning carries his name. Sweet potatoes were a crop he cherished, developing more than a hundred uses and recipes. They also carried African memory — a descendant of yams cultivated for centuries, transformed in the Americas into a staple of survival and celebration.

Sweet potato pie became more than dessert. It became a story passed down at family tables, Sunday dinners, and holiday feasts. With each bite, it whispers resilience, creativity, and joy. This blend is our tribute to Carver’s genius — reminding us that even the humblest root can nourish both body and soul.

The Legacy

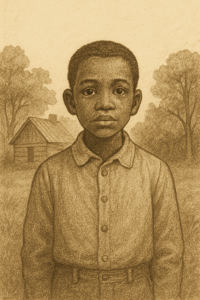

George Washington Carver’s life was marked by hardship, persistence, and an insatiable curiosity about the natural world.

George Washington Carver’s life was marked by hardship, persistence, and an insatiable curiosity about the natural world.

He was born into slavery in Diamond, Missouri, around 1864, near the end of the Civil War. His father, a slave on a neighboring farm, died before Carver was born. His mother, Mary, was kidnapped by raiders when George was still an infant. He and his brother, James, were raised by their former enslavers, Moses and Susan Carver, after emancipation. George’s health was frail, and he was often excused from hard farm labor. Instead, he explored the fields, woods, and gardens, developing an early fascination with plants.

Denied access to most schools because of segregation, Carver’s thirst for knowledge was relentless. He walked miles to attend classes in makeshift schoolhouses, sometimes sleeping outdoors or working as a farmhand to support himself. His determination caught the attention of teachers who encouraged his talent, especially in art. Carver initially enrolled at Simpson College in Iowa to study painting and drawing, with dreams of becoming an artist. His botanical illustrations were so remarkable that his professors guided him toward agricultural science, seeing how he combined artistry with scientific insight.

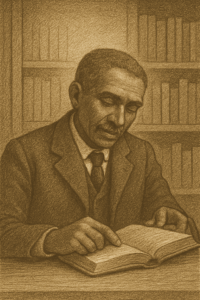

Carver transferred to Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University), becoming the school’s first Black student. There he studied botany and mycology, excelling in agricultural research. His professors recognized not only his brilliance but his humility and spiritual approach to science. Carver often said, “I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting station, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.”

After earning both a bachelor’s and master’s degree, Carver accepted a position at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he would remain for over 40 years. At Tuskegee, Carver developed new ways to rebuild soil depleted by cotton farming. He promoted crop rotation and encouraged farmers to grow peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans — plants that enriched the soil and provided nutritious alternatives.

Carver’s genius was not in hoarding discoveries but in sharing them. He wrote dozens of agricultural bulletins for farmers, explaining simple techniques and recipes that could make the most of limited resources. He became famous for developing more than 300 uses for peanuts and more than 100 uses for sweet potatoes, including flour, adhesives, rubber substitutes, dyes, and sweet treats. Yet he refused to patent most of his work. “God gave them to me,” he explained. “How can I sell them to someone else?”

His commitment to service brought him national fame. He advised U.S. presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin D. Roosevelt, and consulted with industrial leaders like Henry Ford and Thomas Edison. He testified before Congress about peanuts, earning standing ovations. But Carver remained humble, living simply in his Tuskegee dorm room and dedicating his life to his students and his people.

Carver’s story is not one of wealth but of impact. He died in 1943, having received numerous honors, including the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP and the Roosevelt Medal for distinguished service. President Harry Truman later signed a joint resolution making January 5th “George Washington Carver Day,” the first national recognition of an African American scientist.

Carver’s legacy lives on not in patents or profits but in the philosophy he embodied: use what you have, respect the earth, and serve humanity. His work reminds us that innovation and resilience are part of our inheritance.

The Food Connection

Food has always been both survival and celebration in the Black experience. Sweet potatoes, in particular, carry ancestral echoes. In West Africa, yams were central to cuisine, culture, and ritual. Enslaved Africans, stripped of their homelands, found in sweet potatoes a new root that resembled the yam. They turned it into sustenance that fed generations through slavery, sharecropping, and migration.

Food has always been both survival and celebration in the Black experience. Sweet potatoes, in particular, carry ancestral echoes. In West Africa, yams were central to cuisine, culture, and ritual. Enslaved Africans, stripped of their homelands, found in sweet potatoes a new root that resembled the yam. They turned it into sustenance that fed generations through slavery, sharecropping, and migration.

Carver recognized both the nutritional and cultural value of sweet potatoes. He promoted them as a crop that could fight hunger and poverty. His agricultural bulletins included recipes for sweet potato bread, pancakes, pie, and even coffee substitutes. For poor Black families in the South, these ideas weren’t just recipes; they were strategies for survival.

Sweet potato pie, in particular, became a dish of memory and love. Passed down through kitchens and holidays, it transformed from necessity into tradition. Unlike pumpkin pie, which dominated white American tables, sweet potato pie carried the imprint of Black heritage. It became a symbol of Southern identity and diaspora connection, showing up at Sunday dinners, family reunions, church potlucks, and Thanksgiving feasts.

This seasoning blend honors that journey. Its warmth evokes the kitchens where mothers and grandmothers stirred history into every pie. Its sweetness carries the story of how we turned survival food into sacred culture. To taste it is to taste resilience — and to honor Carver, who taught us that food can be innovation, empowerment, and art.

Why It Matters Today

Carver’s lessons are as urgent today as they were in his lifetime. Across America, Black communities face food deserts — neighborhoods where fresh, affordable produce is scarce. The over-reliance on processed, low-nutrient foods has fueled health disparities, from diabetes to hypertension. Carver’s emphasis on growing local, sustainable crops and using them creatively is a blueprint for liberation.

Carver’s lessons are as urgent today as they were in his lifetime. Across America, Black communities face food deserts — neighborhoods where fresh, affordable produce is scarce. The over-reliance on processed, low-nutrient foods has fueled health disparities, from diabetes to hypertension. Carver’s emphasis on growing local, sustainable crops and using them creatively is a blueprint for liberation.

Carver also modeled innovation under constraint. He was not given vast laboratories or million-dollar research budgets. He worked with what he had — clay pots, simple tools, natural curiosity. From those humble beginnings, he produced discoveries that stunned the world. For communities told they lack resources, his life is proof that creativity and persistence are the ultimate wealth.

His philosophy — that service, not profit, defines success — is also revolutionary in a world that glorifies materialism. Carver believed knowledge was a divine gift, meant to be shared freely. That spirit of collective uplift is a reminder for us today to measure success not by what we accumulate but by what we give back.

And then there is the sweet potato pie itself. On holiday tables, it remains a symbol of family and continuity. Each slice is a reminder of how we survived slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and beyond. To bake it today with this seasoning is to participate in an unbroken tradition — one that affirms: we are still here, still creating, still celebrating.

Carver matters today because he showed that Black genius cannot be confined. His life was an answer to every racist stereotype, every effort to erase our brilliance. He proved that what grows from the soil of struggle can nourish generations. And with every bite of sweet potato pie, we keep that truth alive.

Reflection & Table Talk

When you sit down with sweet potato pie seasoned in Carver’s honor, take a moment for conversation.

- Memory: What food connects you most strongly to your ancestors?

- Creativity: Carver created hundreds of uses from one crop. What ordinary things in your life could become extraordinary with imagination?

- Community: Carver measured success by service. How can your family or community live by that principle today?

Food is never just food. It is memory, innovation, and resistance served on a plate. Ask these questions at your table, and watch how quickly history becomes alive in your home.

Call to Action

This seasoning is more than flavor — it’s an invitation to reclaim your story.

That’s why Igotchu Seasonings and Urban Intellectuals joined forces: to remind us that every kitchen can be a classroom, every bite a lesson in resilience.

- 🌱 Collect the full set of seasonings — each tied to a Black history legend, from Georgia Gilmore to Fannie Lou Hamer. Click here to purchase and learn more.

- 📚 Dive deeper with our Black History Flashcards — 52 powerful cards filled with stories like Carver’s, made for families to learn together. Click here to grab a deck.

- 🌍 Start your children early with the Sankofa Club — live and on-demand classes where kids discover Black history, leadership, and pride. Click here to join the club.

Your purchase keeps culture alive — on the table, in the classroom, and across generations. Because food tells our story. Let’s make sure it never goes untold.

Igotchu Seasonings X Urban Intellectuals Collaboration, 4 Flavor Seasonings + History Pack!

Sources / Further Reading

- McMurry, Linda O. George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol. Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Hersey, Mark D. My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver. University of Georgia Press, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. George Washington Carver: In His Own Words. University of Missouri Press, 2017.

- National Park Service. “George Washington Carver Biography.” nps.gov.

- Iowa State University Archives. “George Washington Carver Collection.” digitalcollections.lib.iastate.edu.