Revolution from the Kitchen: Georgia Gilmore and the Taste of Freedom

Extended Readings from the Igotchu x Urban Intellectuals Seasonings Collaboration — honoring the women whose cooking fueled resistance.

Explore Fannie Lou Hamer | Georgia Gimore | Sweet Auburn | George Washington Carver

Igotchu Seasonings X Urban Intellectuals Collaboration, 4 Flavor Seasonings + History Pack!

Introduction

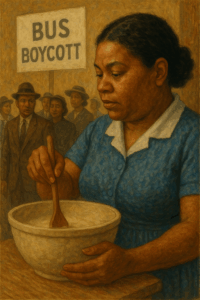

When the Montgomery Bus Boycott began in 1955, one woman found her weapon not in marches or speeches but in her kitchen. Georgia Gilmore, a midwife, activist, and extraordinary cook, fried chicken and baked pies to raise money for the movement.

When the Montgomery Bus Boycott began in 1955, one woman found her weapon not in marches or speeches but in her kitchen. Georgia Gilmore, a midwife, activist, and extraordinary cook, fried chicken and baked pies to raise money for the movement.

Her food was more than nourishment — it was revolution disguised as supper. With every plate sold, she helped fund the carpools that kept the boycott alive for over a year. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. trusted her; the community relied on her; the movement was literally fed by her hands.

This Fried Chicken Seasoning pays homage to Gilmore’s revolutionary kitchen. Fried chicken has long been a dish of resilience, joy, and community gathering, and in Gilmore’s hands, it became a force for freedom. When you season your chicken today, remember the woman whose cast-iron skillet helped change the course of history.

The Legacy

Early Life

Georgia Teresa Gilmore was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1920. She grew up in the segregated South, where Black women were often confined to domestic labor. Gilmore made her living as a cook and midwife — occupations that demanded skill, stamina, and resilience but were undervalued in a racially divided society.

Her early years gave her firsthand experience with the indignities of Jim Crow. Riding buses meant being pushed to the back or forced to give up her seat to white passengers. Jobs were scarce, pay was low, and opportunities for Black women were few. Yet Gilmore was not a woman easily silenced. Her strength, humor, and bold personality made her a natural leader in her community long before the boycott began.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

The arrest of Rosa Parks in December 1955 set off the Montgomery Bus Boycott. For 381 days, Montgomery’s Black residents refused to ride city buses, crippling the system financially while challenging segregation laws in the courts.

The arrest of Rosa Parks in December 1955 set off the Montgomery Bus Boycott. For 381 days, Montgomery’s Black residents refused to ride city buses, crippling the system financially while challenging segregation laws in the courts.

But boycotts require resources. People still needed to get to work, pay bills, and feed their families. The movement depended on carpools and constant fundraising. This is where Gilmore stepped in.

She organized a group of women who cooked and sold meals to support the cause. Together, they became known as the Club from Nowhere. The name was ingenious: when questioned about where the money came from, leaders could say truthfully, “from nowhere.” This protected the women from retaliation while funneling steady funds into the boycott.

Feeding Freedom

Gilmore herself fried chicken, baked pies, and cooked vegetables in her home kitchen. She sold food at beauty salons, barber shops, and community gatherings. Her meals raised hundreds of dollars each week, covering gas for the carpools, legal fees, and other movement costs.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became a regular at her table, often eating Gilmore’s food during late-night strategy meetings. Other leaders, including Ralph Abernathy and E.D. Nixon, also relied on her cooking and support. Gilmore was more than a cook — she was a strategist, fundraiser, and morale-builder.

Her courage was tested in 1956 when she testified during King’s trial for conspiracy to boycott buses. In front of an all-white jury and hostile officials, Gilmore declared that she had been denied service on buses because of her race. Her plain-spoken testimony — delivered with humor and fire — cut through legal jargon and made injustice undeniable.

Later Years

After the boycott ended with a Supreme Court ruling that segregation on buses was unconstitutional, Gilmore continued her activism through food. She ran a thriving home restaurant out of her kitchen, serving fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, and pound cake to neighbors and civil rights leaders alike.

Her house became a hub of community gathering and organizing. Even after the height of the civil rights era passed, Gilmore’s kitchen remained a place of refuge, storytelling, and nourishment. She died in 1990, but her legacy endures as proof that the fight for justice is fueled not only by speeches and marches but by meals prepared with love and purpose.

The Food Connection

Fried chicken has a long and layered history in Black culture. Its roots trace back to West Africa, where chickens were seasoned with spices and fried in palm oil. Enslaved Africans carried these techniques to the Americas, where they adapted them with available ingredients.

Fried chicken has a long and layered history in Black culture. Its roots trace back to West Africa, where chickens were seasoned with spices and fried in palm oil. Enslaved Africans carried these techniques to the Americas, where they adapted them with available ingredients.

In slavery and beyond, fried chicken became both sustenance and symbol. It was often one of the few meats enslaved families could raise and prepare themselves, and it became a dish associated with special occasions, Sunday dinners, and communal gatherings. After emancipation, Black women often sold fried chicken at markets, fairs, and roadside stands to earn independent income in a hostile economy.

By the time Georgia Gilmore was frying chicken for the boycott, the dish carried centuries of meaning: survival, ingenuity, and economic independence. Her seasoning, skill, and frying pan transformed it into a tool of resistance.

Today, fried chicken continues to carry cultural weight. It is sometimes caricatured by racist stereotypes, but in truth, it is a dish of pride, heritage, and joy. In Gilmore’s hands, it was a weapon of liberation, proving that food itself could be revolutionary.

Why It Matters Today

Georgia Gilmore’s story reminds us that every gift can be used for freedom. She didn’t write laws or deliver famous speeches, but her fried chicken was just as essential to the boycott as rallies and court cases. She demonstrates that movements succeed because of countless acts of everyday courage.

Her story also speaks to the power of Black women’s labor, often erased from history. Kitchens have long been spaces of both oppression and power. In Gilmore’s case, her kitchen became a war room for liberation, where grease popped and resistance simmered alongside collard greens.

In today’s struggles — from racial justice to food insecurity — Gilmore’s legacy teaches us to use what we have. Whether it’s a skill, a space, or a recipe, every resource can be turned toward freedom. Her fried chicken reminds us that resistance is not only about confrontation but also about community, nourishment, and joy.

Reflection & Table Talk

-

How can we transform our own skills into tools for justice, as Georgia Gilmore did?

-

What role has food played in your family’s stories of survival or progress?

-

How do we honor the labor of Black women, often invisible yet essential to every movement?

Call to Action

This seasoning is more than flavor — it’s an invitation to reclaim your story.

That’s why Igotchu Seasonings and Urban Intellectuals joined forces: to remind us that every kitchen can be a classroom, every bite a lesson in resilience.

- 🌱 Collect the full set of seasonings — each tied to a Black history legend, from Georgia Gilmore to Fannie Lou Hamer. Click here to purchase and learn more.

- 📚 Dive deeper with our Black History Flashcards — 52 powerful cards filled with stories like Carver’s, made for families to learn together. Click here to grab a deck.

- 🌍 Start your children early with the Sankofa Club — live and on-demand classes where kids discover Black history, leadership, and pride. Click here to join the club.

Your purchase keeps culture alive — on the table, in the classroom, and across generations. Because food tells our story. Let’s make sure it never goes untold.

Igotchu Seasonings X Urban Intellectuals Collaboration, 4 Flavor Seasonings + History Pack!

Sources / Further Reading

-

Williams, Jeanetta D. Georgia Gilmore and the Club from Nowhere: Women’s Grassroots Leadership in the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

-

McGuire, Danielle L. At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance. Vintage, 2010.

-

Washington Post. “The Unsung Heroine of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.”

-

National Civil Rights Museum. “Georgia Gilmore: The Club from Nowhere.”

-

Kotz, Nick. Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Laws That Changed America. Houghton Mifflin, 2005.